Lakers-Celtics, an eternal war for the NBA throne

From Frank Selvy's miss to Jerry West's bitter MVP; the Memorial Day Massacre, the heat game, Magic Johnson's junior sky hook, Gerald Henderson's steal of James Worthy, the evolution of the Celtics' big three from Larry Bird, Kevin McHale and Robert Parish to Paul Pierce, Ray Allen, and Kevin Garnett; the redemption after very painful defeats of the two greatest idols that the Lakers fans have had, Magic Johnson and Kobe Bryant... The battles between the Lakers and the Celtics resonate in the bones of American sports, sink their roots in the prehistory of basketball and spin a tradition that surely saved the NBA. Or, at least, it turned it into the extraordinary competition we live with now.

At the level of the Packers-Bears in the NFL, the Yankees-Red Sox in the MLB or the thousand pending accounts of university sports, from Duke-North Carolina in basketball to the football fields: Michigan-Ohio State, Texas -Oklahoma… the rivalry, from coast to coast of the country, between the Lakers and Celtics is a race of more than six decades for the NBA throne, one that has elevated and differentiated them from the rest. An extra category: 17 titles for the Celtics, 17 for the Lakers. No other franchise has more than six. And twelve Finals in which they have faced each other face to face, with everything at stake. In 1963 the Celtics overtook the Lakers (six titles to five) after a 4-2 in the direct duel of that Final. Since then, the Greens had held the throne with an advantage that reached 14-6 in 1976. But the Lakers' last title, that of LeBron James and Anthony Davis in the Walt Disney World sanitary bubble, has placed some historical tables, seventeen battles for each one in a fight that never ends. A fight for hegemony. It is the great eternal war of world basketball, and this is its story.

1.- It all started again in Salt Lake City Answer

2.- Choose your weaponAnswer

3.- The path to perfectionAnswer

4.- The birth of the Beat L.A.Response

5.- Lagos, Russell and the first dynastiesAnswer

6.- Kobe Bryant against the Big 3Answer

7.- Celtic spark in CaliforniaAnswer

8.- A story made from storiesResponse

It all started again in Salt Lake City

Actually, it all started, at least as we understand it now (it came back), on March 26, at the Special Events Center in Salt Lake City. The capital of the Mormon state, Utah; a small city of less than 200,000 inhabitants, between the desert and the mountains, anchored in a tiny market and, of course, without a great basketball tradition. In December 1975, the ABA had terminated the Utah Stars, a team that won the title in 1971, as soon as they moved from Los Angeles, and which was literally penniless and died at the gates of the NBA-ABA union that, in 1976 , sent four surviving franchises to the Mother League: Denver Nuggets, Indiana Pacers, San Antonio Spurs and New York Nets.

In that March, the transfer (as of the following season, 1979-80) of the Jazz from New Orleans was about to be announced, where economic problems forced the move, not at all something exotic in professional basketball in so. With no time to request and polish the makeovers that would have been necessary, the franchise retained the Jazz music name and Mardi Gras colors (yellow, purple, green) even though it went on to play in Utah, where the Jazz and Mardi Gras resound so far away.

In that 1979-80 season, the three-point shot arrived in the NBA, and Magic Johnson and Larry Bird arrived. And everything changed. Interestingly, those Jazz could have Magic, but in 1976 they had given their first rounds of 1977 and 1979 to the Lakers as compensation, in a time when free agency did not exist as such, to sign Gail Goodrich, an excellent point guard who He had formed an outside partner with Jerry West on the 1972 champion team and had already played his best years of basketball. The Jazz surely did not imagine that they would be so bad in 1979 and that their pick would be so valuable in that draft, precisely, in which a player who would transform the history of basketball and who ended up in the Lakers thanks to that operation and a coin toss. This is how the number 1 draft was resolved between the worst teams in the West (Chicago Bulls before their change of Conference) and East (the asset of the Lakers inherited from the Jazz). Luck smiled on the Lakers, who took Magic Johnson.

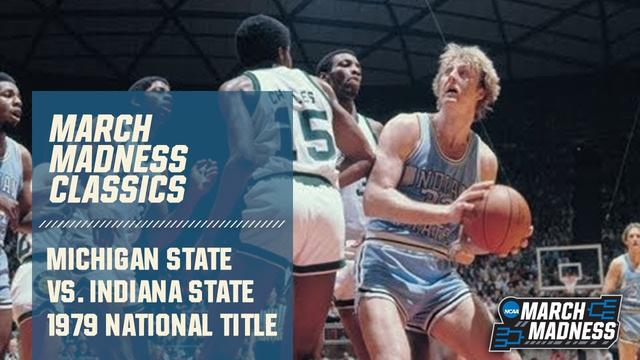

Magic threw out on March 26, 1979, in the most-watched university final in history, his first great fight against Larry Bird, who would be his nemesis during his career and, finally, an inseparable friend. He was elected Best Player of the Final Four and there, at the University of Utah facilities, his Michigan State Spartans beat (75-64) the Indiana State Sycamores, Larry Bird's team that arrived undefeated (33-0 ) to a final broadcast on NBC and which was followed by 20% more viewers than that of 1978 and brought together almost 40 million people with a rating that exceeded 24%. The never seen.

15,000 people, at an average of $15 per ticket and with only 5,000 seats released by the NCAA for Salt Lake City fans, watched the prologue to one of the greatest stories in sports: Magic Johnson scored 24 points and grabbed 7 rebounds and Bird added 19+13 but stayed at 7/21 in improper shots on him. He was 22 years old to the Magic's 19, and in his case he had already been drafted a year earlier, in 1978. A frustrated 24-day stint at Indiana University, where he arrived with $75 and barely any clothes, before returning to his town, French Lick, upset him greatly with his mother (until a year later she left for Indiana State) and made him legally eligible for the 1978 draft. He was scouted by the Pacers, the team from his native Indiana , but they sent their number 1 to the Blazers, who tried to convince him in every way imaginable, including people who approached him on the street to advise him to go to Oregon. With the newly acquired 1 and the 7 already owned, their move was clear: they chose Mychal Thompson first, born in the Bahamas, the first non-American number 1 in history... and future Magic teammate in the Lakers. But for his second election, Larry Bird was no longer there: the mythical Red Auerbach, the great legend of the Celtics, took him with the 6 without having spoken to him once.

Magic and Bird arrived in the NBA together at the start of that 1979-80 season that changed everything. They drew the attention of the entire country, admired by that clash of styles that had been waged in Salt Lake City and attracted by the fit of both in the Lakers and Celtics, who had been bitter rivals in the 60s. collisions, Bill Russell and Wilt Chamberlain had left, the NBA had gotten into disputes with the ABA and was considered by the general public to be too black a League with a rampant drug problem: according to an article in the Los Angeles Times in 1980 , between 40 and 75% of NBA players consumed them, in many cases with a clearly addictive pattern. Simon Gourdine, the great African-American manager in professional sports in the 1970s, warned as the commissioner's right-hand man that, once again, race accusations were being aired: already at that time (and as now) 75% of the players NBA players were black, a number that was suspiciously consistent with the data provided by the Los Angeles Times article.

David Stern, who became commissioner in 1984 and served until 2014, had no problem blaming drugs and racial bias for the bad times he lived in a competition with half-empty stands, without a television contract viable and with games broadcast on deferred, even in the Finals. Tickets in 1979 cost an average of 50 dollars, something that was seen as excessive for families who viewed with suspicion how the salaries of the players stood at an average of 130,000 dollars a year, with a minimum of 30,000 and the top in the million. Among the white population of the residential neighborhoods, an NBA that had been running out of great references of its race did not take hold; a League with 198 African-Americans, 73% of the total players (273) in the (then) 22 franchises. The first eleven picks in the 1979 draft went to black players, and in that training camp the Knicks fielded the first all-Afro-American team in history. “That is not a problem here, in other places it would be. In a city like Boston it would be a good problem", they said from the offices of the Big Apple, where the least influx to Madison was seen as the simple effect of the competitive slump of a team that came from glory and rings at the beginning of the decade. A legendary roster that had two white forwards in its starting five (Bill Bradley and Dave DeBusschere) but three big black stars: Walt Frazier, Earl Monroe and Willis Reed.

The NBA was not only frowned upon by the well-to-do white community: educators in mostly African-American inner-city areas were openly suspicious of a sports success culture that offered an elixir of glory and wealth that only a few had access to. Paul Silas, then president of the players' union, led the League's first efforts to engage with those communities and reconnect with the neighborhoods from which, in essence, so many of its players came: "We know that in the NBA there are 240 players and in the United States more than 240 million people. So we are clear that we are one in a million”. The players also viewed with concern the fall in audiences, the bald spots in the stands of the pavilions and the bad press that accompanied the League and them, its great protagonists.

But in 1979 came Bird and Magic. The collision of two ways of living, playing and showing themselves to the world. Magic's smile, Bird's sullen silences, who before his famous university duel already referred without any sympathy to the rival who was going to mark his entire career: “He smiles playing but I don't. When you're tied and there's little time left, you can't smile. It seems that he laughs at his rivals… I just hope he doesn't laugh at me”. One white and one black, one in the Lakers and another in the Celtics, the great duel of the long-awaited sixties, the collision of the two coasts, East vs. West. An enigma against a showman, mystery against charisma and two extraordinary players, who transcended their positions on the track (point guard and forward) and who ended up changing the history of the sport and turning the NBA into a modern, rich League launched into a future that then he took the phenomenon Michael Jordan into hyperspace. But everything, the rivalry that saved the NBA, had started in Salt Lake City on March 26, 1979.

From hate to friendship: choose your weapon

Bird and Magic met for the first time in the NBA on December 28 of that 1979, at the Forum in Inglewood: 123-105 for the Lakers, 23 points, 8 rebounds and 6 assists for Magic, 16+4+3 for Bird. At the end of that first season for both, the Celtics took the Rookie of the Year award but Magic took the ring and the MVP of the Finals at just 20 years and 276 days (prematurity record that is still valid). That first game in California was played nine months after the university final and in an NBA that was going to leave behind a decade in which only one game had made it into the top ten most watched on television: the 1974 Finals, between the Bucks and Celtics. The rest was the domain of the College by crushing. The Dallas Mavericks would arrive a year later, in the 1980-81 season, putting up 12 million dollars to pay for an expansion that forced the Hornets (then Bobcats) to pay 300 million in 2004. The progression is obvious.

CBS broadcast most of the games delayed because the audiences did not invite anything else and Stern had not started his revolution: marketing, merchandising and exploitation of the pavilions as integral leisure centers. But nothing would have worked, not at the level at which it ended up working, without the stars, some referents that occupied what had come to seem like empty space. Due to Bill Walton's injuries and the little collective success that Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, extraordinary but without much charisma or a good public image, experienced in his early years with the Lakers... until, in fact, the arrival of Magic Johnson, a lone gamer who'd gotten his nickname while he was still playing in high school in Lansing, in tough Michigan where his father worked night shifts for General Motors. Less than 600 kilometers away, in the much more rural French Lick of Indiana, Larry Bird had an austere childhood in a very different family but in which nothing was left over.

So before the Magic embraced and embodied the glamor and essence of Hollywood, they were both players from blue-collar America, the deep, blue-collar roots of the country, emotionally far removed from Boston and far removed, in every way. , from sunny California. Two promises of better times and two faces of the same America, even if it was hard to believe. Together, before the university final and the sick rivalry in the NBA, they shared a team fourteen years before the Dream Team and the definitive explosion of the global NBA starting in Barcelona 92. It was in 1978 and during that time he invented what was the WIT (World Invitational Tournament), in which a selection of American university students played matches against Cuba, Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union from Georgia to North Carolina and Kentucky. In Lexington, in the illustrious home of the Wildcats, Magic and Bird shared the bench as part of the second unit of the team led by Joe B. Hall. From that concentration they returned enthusiastic about each other: "That white guy is really good, the toughest player I've ever seen" Magic told his relatives; "Back then he was the best point guard on the team," said a Bird who spent hours gazing intently at the Kentucky landscape while the Magic made friends with Sidney Moncrief, the Arkansas star who was number 5 in his draft, the one in 1979, and who triumphed in the Bucks, where he was an all-star five times and where he won the first two editions of the Defender of the Year award.

The evolution of the relationship between the two stars, the two figures who polarized and propelled the NBA to infinity, is an exciting mix of emotions, competitiveness pushed to the limit and a respect that first expressed itself in a perfectly visible hatred and then in a friendship that ended with Magic in the center of the Garden and wearing the Celtics jersey at Bird's retirement ceremony. He had recognized that for years the only thing he looked at in the morning was Magic Johnson's statistics, which in turn was very clear when he spoke of his great rival: "I hated him even more when I realized that he was the player I always wanted." I could win."

In 1992 Bird and Magic played together in Barcelona, sponsors along with Michael Jordan of the best team ever assembled, the Dream Team that fell in love with the world and definitively transformed the NBA as a market with an international focus. The Jordan era had begun. Bird had a seven on his back, and actually retired after the Olympics, and Magic was playing less than a year after announcing to the world that he was HIV positive. It was on November 7, 1991, after losing the Final against the Jordan Bulls that they released their record, and it was one of the most momentous events in the history of American sports. Magic, who had discovered the infection in medical tests prior to the 1991-92 season, then became a crucial ambassador for the fight against AIDS, both the disease and the prejudices and misinformation that fueled it. Among the handful of close friends he called to give them the news in the first person before appearing before the press, the name of his great friend and old enemy, Larry Bird, stood out.

“We've been connected since college. We've spent our lives thinking about each other. I knew that he would want to hear the news from me, I knew that he would want to know that everything was going to be okay and I knew that he was going to support me, "said Magic, who was about to get Larry Bird to break, the unbreakable guy:" It's one of the worst moments, one of the worst feelings I have experienced. It was very difficult. At the time, we believed that HIV was a death sentence. But when he told me it would be fine I believed him, basically because he always followed through on everything he said when he played, whether it was winning games or winning championships. I loved basketball, I spent the day wanting to play, train… but after that call it was the only time in my entire life that I didn't want to know anything about basketball”.

From Salt Lake City in 1979 to the call to Larry Bird before his dramatic announcement in 1991, twelve years had passed, set on a perfect axis by a quiet September 12, 1985 in West Baden, next to the hometown of a Bird nicknamed The Hick From French Lick. That day, enemies became friends in the simplest way: sharing a table at the home of Georgia Bird, a mother who greeted Magic with hugs, iced tea, lemonade, fried chicken, and cherry pie when the Lakers star arrived at the Deep Indiana in an entourage of three limousines. Converse, which had both under its belt, worked hard to get them to commit to doing an ad together. Those were times when marketing was in its infancy and few players had a personal shoe contract. "Choose Your Weapon" (choose your weapon) was a mythical campaign of that brand to sell its new model with two formats, one with the colors of the Lakers and another with those of the Celtics. The two teams that already dominated the NBA and, increasingly, the world. It was a matter of each one choosing sides... and shoes.

Bird was consumed by that encounter because he believed it was not good to get too close to the great rival he had faced in two consecutive Finals (won 1984, lost 1985). Magic, because he didn't know how the cantankerous Bird would react and feared that his trainer, the mythical and hyper-competitive Pat Riley, would fly into a rage over what he would surely consider an unnecessary fraternization with the enemy. To avoid an announcement, Bird demanded that it be shot in his hometown of rural Indiana. To the surprise of the Celtics' 33, Magic agreed, asked for more money for everyone and went on a trip that changed his life forever. On the way to the house of the mother of his great rival, he discovered a landscape not very different from that of his native Lansing. And as soon as, sitting at the table, the ice broke, the two saw that in reality, and as incredible as it might seem, they were not so different: children of the Midwest, from very humble families, parents who worked hard and with more at their fingertips than they could have ever imagined just by playing a sport that any child could play. But, yes, for practicing it like no one had done until then in all of history. Choose your weapon.

Five Great Lakers Coaches

The path to perfection

Magic Johnson arrived in 1979 to a Lakers who had just won 47 games and played in the Western semifinals with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Jamal Wilkes, Norm Nixon and Adrian Dantley who went to the Jazz to make room for Spencer Haywood, the star who fell from grace, succumbed to drug hell and ended up plotting to assassinate the coach who led the team to the title in 1980, Paul Westhead. It was a team with a lot of talent but no vital spark that added a budding megastar, Magic, who was not a vital spark: it was the Big Bang. Larry Bird inherited a very different situation. Three years after the 1976 ring, the Celtics were a block that had gone two years in a row without a playoff, the last with only 29 victories. From there they jumped to 61 and a place in the second round of the East, where they fell against some tremendous Sixers (Julius Erving, Darryl Dawkins, Lionel Hollins, Bobby Jones, Mo Cheeks...), the closest rival in their Conference.

In that first season, Bird averaged 21.3 points, 10.4 rebounds, 4.5 assists, and 1.7 steals. And he was voted Rookie of the Year. Magic finished at 18+7.7+7.3+2.4 and signed in the Finals, against the same Sixers who had pushed Bird out of his way, one of the most prodigious feats in the history of the fight for the ring . In Philadelphia, Comanche territory, and with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar out due to an ankle injury, the rookie from Michigan State started the game as center, played in all positions and decided the title (4-2) with 42 points, 15 rebounds and 7 assists towards the MVP of the Final.

It was the first of ten consecutive Finals (1980-89) in which either the Lakers or the Celtics were always involved. The Angelenos played eight, which only left room for the Rockets (who lost in 1981 and 1986 against the Celtics). And five the green ones, who were slipped three times by the Sixers and twice by the Detroit Pistons Bad Boys, the team that closed the happy 80s and led an NBA no longer innocent to the steel battles of the following decade, the industry heavy on which Michael Jordan made poetry. The Lakers won five rings (1980, 1982, 1985, 1987 and 1988) and the Celtics three (1981, 1984, 1986). And, above all, they faced each other in three tremendous Finals (1984, 1985 and 1987), the first with a victory for those from the East and the next two with a revenge against the Californians, who began a hunt there that did not end until 2020, in the Florida bubble and with LeBron James at the controls: 17 rings for each one, the two united in the highest of a list of winners in which they are followed, far away, by the Golden State Warriors and Chicago Bulls (6).

By the summer of 1986, the Celtics had played in 18 Finals and won 16, a prodigious ERA. The Lakers were a rough 9 of 20, self-conscious about a rival they had finally beaten in 1985 (and would win again in 1987) after eight straight losses, seven between 1959 and 1969. Since that 1986, the Celtics have only won the 2008 title, precisely against a Lakers who have added eight more between 1987 and 2020, including the 2010 one in which they defeated the Celtics for the first time in a seventh game. The balance in direct confrontations is 9-3 (for those from Massachusetts, of course) in twelve series for the ring. Five of them went to seven games and ten to a minimum of six. Gigantic collisions that are the flesh and bones of the NBA: between the two colossi they have 34 rings out of 74 total: 45% of the seasons played to date have ended with a victory for one or the other. The eternal war.

During that decade of the 80s, the United States fell in love, again and more than ever, with an NBA that stopped being televised on a delayed basis and that jumped onto screens all over the world: in Spain in 1988 with the unforgettable “ Close to the Stars” on TVE. The arenas filled and every game between the Lakers and the Celtics was a fight for the status quo, a fight for survival, a fight between two ways of life waged by two rivals who tried to rewrite their history and, in doing so, changed that of the american sport. And that they grew up obsessed with defeating the other, with always being prepared, with having weapons to counteract the ones they knew were going to be used against them. This is how they each forged the best version of themselves and two of the best teams that have ever set foot on a basketball court: the Celtics champions in 1986 and the Lakers who took the title in 1987.

SB Nation held a bracket during confinement with which they intended to decide which was the best team in history for NBA fans. In parallel, he added all the possible variants to determine his own list, more scientific, regardless of the one he was going to throw, with pairings until he found a champion, the popular vote: points, offensive and defensive ratings, potential of his rivals in that entire season, playoff victories, number of MVPs and all stars... fans chose the 1996 Bulls (the year of Michael Jordan and company's 72-10) over the team favored by SB Nation accounts: the Warriors from 2017; the best version of the Stephen Curry-Klay Thompson-Andre Iguodala-Kevin Durant-Draymond Green axis, the megadeath quintet. The 1972 Lakers had stayed in the semifinals, the team that broke the spell in L.A. with Jerry West and Wilt Chamberlain, and the 1986 Celtics, who had precisely defeated the 1987 Lakers in the previous round, crossover things. In the scientific list, the 2016-17 Warriors appeared as the best champion ever and the 1986 Celtics were second, ahead of the 1996 plus-perfect Bulls. The 1987 Lakers were seventh.

In 1987, the Lakers and Celtics met for the last time in the Finals until 2008. It was the Lakers' second straight win, after 1985, after eight consecutive losses against their hated rival. The definitive end of the complexes. A year earlier, the Rockets of the twin towers (Hakeem Olajuwon and a Ralph Sampson for whom the Lakers had longed when he was leaving Virginia) avoided the third consecutive Final between purple and green with four consecutive victories against some speechless Lakers: from 1-0 to 1-4 with a final basket by Sampson, absolutely miraculous, to consummate the rebellion in the fifth game.

So the Celtics, who had won in '84 and lost in '85, reached the 1986 Finals but this time they didn't meet the Lakers there, a disappointment for a Larry Bird who fanned the Rockets ( 4-2) with 24 points, 9.7 rebounds, 9.5 assists and 2.7 steals per game. In his last prime before back problems led to martyrdom, Bird (on his way to 30) won his third ring, his third MVP in a row, his second Finals MVP, his first 3-point contest (he also took his second and the third) and was named Sportsman of the Year by the Associated Press. Also, of course, he was an all-star and member of the Best Quintet of that 1985-86 season through which the Celtics went through like a whirlwind: 67-15 total and 40-1 at home (a mark that was equaled by no one until the Spurs in 2016 ), with 37-1 at the legendary Garden and 3-0 at the Hartford Civic Center. And 11-1 for the Eastern playoffs, with sweeps of the Bucks in the finals and the Bulls (3-0) in the first round, including the legendary Michael Jordan 63-point game in which Bird said he had seen in the Garden to "God disguised as a basketball player." They won, after two extensions, some armored Celtics and Jordan tested.

KC Jones, who as a player had won eight rings with the franchise, led a near-perfect team and became the second African-American coach with more than one ring won on the bench. The other is Bill Russell… also with the Celtics. The excellent but more volatile team of years before (Tiny Archibald, Cedric Maxwell, Chris Ford, Gerald Henderson…) had given way to the martial version of a quintet all the fans memorized: Dennis Johnson, Danny Ainge, Larry Bird, Kevin McHale and Robert Parish. And on the bench Jerry Sichting, recently arrived from the Pacers, Scott Wedman (all star in 1976 and 1980), Rick Carlisle (today one of the best coaches in the League) and, of course, Bill Walton, the red giant who was chosen Best Sixth Man after being MVP and Finals MVP in 1978 and 1977, with the Blazers.

The forging of that powerful champion was a sum of great blows from Red Auerbach, the patriarch who built, one of the pillars of the modern NBA, the great green dynasty of the fifties and sixties. Transferred to the offices, he went first to take Bird before his last year at Indiana State, and in 1980 he engineered one of the best transfers in history: he gave the Warriors the number 1 draft (it was Joe Barry Carroll) who He had thanks to the Pistons along with another first-round pick (13: Rickey Brown) in exchange for the first round of the Bahia (number 3) and a center who had been in Oakland for four years. The pick was Kevin McHale, the center was Robert Parish. The big three Bird-McHale-Parish continues to be one of the most feared frontcourts in basketball history, in that season supported from the bench by Bill Walton, the only one who can challenge Kareem Abdul-Jabbar for the throne of best university player in always and a legendary project that injuries destroyed... but they respected in that last magical year, in Boston. Auerbach ignored his doctors and took him, something that Jerry Buss did not dare to do in the Lakers, giving the Clippers in exchange Cedric Maxwell (MVP of the 1981 Finals) and a first-round pick that ended up becoming , already in the hands of the Portland Trail Blazers, in Arvydas Sabonis.

Knowing that his team's options would end up stopping point guards like the devilish Andrew Toney of the Sixers and the incomparable Magic Johnson, Auerbach had gotten hold of Dennis Johnson in 1983, an exceptional defender and big point guard and very strong that he had been MVP of the Finals in 1979, with the Supersonics. Danny Ainge, finally, was a perfect target in the draft: selected in the second round, number 31 in 1981. Those Celtics were a perfect symphony, a terrifying defense with an endless frontcourt and two bulldogs on the outside; and a collective and harmonious attack in which the ball flew with Bird as the origin and almost always also as the destination. The best defense and the third best attack of the 1985-86 season and a block that added 82 total victories between the Regular Season and the playoffs, a record at that time. And that a year later, in 1987, he lost in the Finals against some super-perfect Lakers.

Ever wondered how to become a dietitian and how we make a difference? Hear from a panel of amazing dietitians from… https://t.co/138IBbPDnX

— BDA Diabetes SG 💙 Wed Jun 02 07:57:05 +0000 2021