Jesús Fernández Úbeda: "Poetry has become a refuge for lazy writers"

Those who know and love Jesús Fernández Úbeda will forgive me for calling him a liar. Jesus is a liar. At the beginning of this year he told me that he was somewhat scattered, that it was the first time in a long time that he did not have any great objective —a book under construction, a new journalistic adventure— with which to fill the days with that enthusiasm that they always bring. future promises. I saw him and I didn't believe him because there, musty as he said he was, he continued to publish articles and interviews at that devilish pace that is so difficult to match. He explained to me that the literary drought he suffered during confinement was too bitter an experience to allow himself to be swept away by it again, and that is why he put the impetus into writing anything, whatever allowed him to continue on the wheel. Shortly after I found out that he published his second collection of poems, the third book signed with his name after Crash Landing and Don't give the dog more whiskey. The revelation did not surprise me. After all, I have already said that Jesus is a liar. uncivil state. Concert of shrikes (Huerga y Fierro), this one that you are now publishing, could give me a little reason on that. His commitment to metrics, in a world dominated by free verse, should be understood as a declaration of intent. But it is necessary to reread what is in there to understand better. Although, if we are to review the book, it is better for him to explain it to us. We start.

Question: What differentiates a liar from a liar?

Answer: (laughs). Well, I would tell you that a liar is a liar facing the gallery. He wears the lie like a showcase. The liar, on the other hand, has one more point of pedigree. He carries the lie in the genetic code. And he can even lie to himself or, even more, believe his own lies. The liar no. The liar is a stockbroker.

Q: Can a liar be a poet?

A: Yes. Obviously. In fact, I think poetry is the most wonderful lie in the world. Or, better said, poetry, when it's a lie and done well, is the most wonderful lie in the world. As Knausgard says, melancholy or despair, in themselves, are not pretty things. But a text that knows how to talk about it in the right way, yes. Elegance, style, rhythm, music always play an important factor there. These are questions that can turn a lie into something beautiful. That is why the great poems of heartbreak, and the great songs, console. What they do process is a terrible truth. A heartbreaking truth, sometimes. But they make it into a palatable and digestible lie. And that, well, welcome.

Q: Sure. These initial questions have arisen from some of your verses: "There are more than a hundred lies, / post-truths, imbalances, / that the shrike shows in its song."

A: Yes, yes. Look, the shrike is a little bird. In Spain there are three species: the royal shrike, the common shrike and the red-backed shrike. It is a very pretty bird, apparently innocent, that what it does is imitate the song of other birds. As the prey approaches, the shrike, perhaps little larger than a goldfinch, attacks it, kills it, and impales it. In this way he builds his particular pantries. Shrike larders are very curious because in them you can see everything: goldfinches, mice, birds, insects. It is a lying bird. In the book there is a lot of lies and there is a lot of truth. The cliché says that the worst lies are half-told truths. And here there are many of those truths, intermingled with each other, to give rise to literature.

Q: In the poem It's better this way, in fact, you seem to rectify or retract certain things written in the previous poems focused on heartbreak.

A: Yes, we will see. The first part of the poems, which is Estado incivil, narrates how a relationship begins very well, how it cools down, how it is poisoned and how it is going to be taken for granted. Also how, once he has gone to be taken for a sack, the protagonist wants to recover that relationship. The truth is that I don't know if I have a narrative collection of poems left, but what I have certainly tried is to have a beginning, middle and end. The leading woman, to whom the poems are directed, seems to be only one, but in reality it is not a single woman who has inspired them. She's a concoction of all the girls I've been bad with in the last two years. What is certain is that the red button, so to speak, the spark that inspired me throughout the development of the poems, is a very specific relationship that I wanted to leave but she did not. Delve into that. The moment when you try to prolong something, out of pity or lack of courage, or because you really hope that time will solve it, but no. In the end, of course, see you later, Lucas. I find it an interesting perspective because, in general, heartbreak songs and poems tend to speak from the perspective of the left. His message is always either "what a whore you are" or "how much I miss you". Not here. Here the bastard is me.

Q: Let's talk about youth. In your collection of poems it appears, for example, in Good afternoon, youth. And it is a topic that is now very fashionable, with all the controversy that was generated with Ana Iris Simón's book. Does our generation have a harder time settling down?

A: Poof. I'm lazy about these issues, really. I could not tell you. I think my approach to youth is different. I treat it from another perspective. In different parts I talk about age disorders, rather. (Laughter). It is a fact that the body gives for what it gives. When you are in the race you can connect three or four days leaving until seven in the morning and the next day, even being in pieces, with a nap you resuscitated. Now that is unthinkable, of course. Now I go out one night until 4 and the next day is a lost day. As for settling down… Well, the expert is Ana Iris.

Q: But then you also have poems that deny that a bit, right? As if you wanted to make it clear that you still have sane.

A: Yes, obviously. What happens is that the string readjusts. I don't see myself as a Carthusian. And now we are in the Plaza del Dos de Mayo. If you walk a little further there, towards San Vicente Ferrer, and turn left, there is the Ocean Rock Bar, owned by my friends Víctor and Alberto. If you don't see me there one day a week it's because maybe something has happened to me.

Q: What is youth?

A: What is youth? (Laughter). Well, for starters it's a physiological state. (Think). I don't say "good morning, youth" or "good night, youth." I say "good afternoon, youth". At 32, I consider myself, to begin with, an adult. It is an adjective that is very much in disuse. Nobody wants to be an adult now. No, no, I am a young adult. But an adult less and less young. An adult who is less and less worried about going out at night to flirt and more worried about doing bills to pay his mortgage.

Q: Is the mortgage the new marriage? I mean as a rite of passage to adulthood.

A: I don't know if it's the new marriage, but at least it's the new proposal to the father. (Laughter). I mean, the mortgage changes your life, man. My student flat was something else. Rare was the week that there was not a mini bacchanal there. Now in my house not even God enters. (Laughter). Or not. I don't know. It's just that I don't even celebrate my birthdays at home anymore, to tell you the truth. Because when she did the same thing she was more aware of whether a drunk asshole dropped his glass than enjoying the party. The mortgage of a house increases the degree of demand. One has less license to do the goose. I left my previous landlord the phenomenal apartment, eh, everything must be said. But it is true that when the house is not yours you are less aware. (Think). Answering your question, one ceases to be young when he delimits his cage more. As golden as it is. In other words, I don't feel like putting a lot of people in my house. And I do think that goes with age. I couldn't share a flat right now. They are degrees that are overcome with life.

Q: Let's talk about another poem: Deserter. Is it a cover letter?

A: Ha. "I'm not from the tribe / I don't have a card." People who have read the book have had a lot of influence on that poem. Many have felt identified, something that congratulates me. It is a poem about me and about my profession. Or about how I deal with certain aspects of my profession. I think that in journalism there is a lot of tribe and a lot of mafia. The journalists who follow "A" tend to occupy some outlets and those who follow "B" tend to occupy others. And if a journalist from group "A" says something outrageous, automatically, all his friends from the same group come out to defend him, even if he has said the most unjustifiable thing in the world. It's normal, of course. One is hired as head of opinion in one place, or of culture in another, and he takes his friends with him. But I can't handle that, man. I don't know how to digest it. One good thing that I think has given me the fact that I have been working for ten years at Libertad Digital is that, being such an anarchic medium, which goes so much on its own and has not needed pacts and that kind of thing, somehow form has impregnated me. So I can have friends in Mongolia —both Edu Galán and Darío Adanti I call them friends— as friends in the right spectrum of the national media scene. I can call Carmelo Jordá or Jorge Bustos a friend. But don't pigeonhole me. God free me. And this is not being center centered or whatever you want to call it. No. This is being outside. I just don't want to belong to any fucking tribe. It is not a position that allows me to be financially buoyant, of course. But I can pay my bills, my mortgage and from time to time I can catch a plane and go abroad. With that I am happy.

Q: What is the price of independence?

A: I don't think it's that tall. It doesn't seem that difficult to me. For me it is a matter of humility. In the end, if you want to have 70,000 followers on Twitter, sell yourself to the devil. But what is Twitter? Then you go and swerve into that herd and the herd pushes you away. And then maybe another tribe will come and pick you up. Or not. Because it does not forget the services you provided.

The garlic was not roasted but my brain certainly appears to be😂😂 both roasted and rusted. https://t.co/HpcfpdjauI

— Tara Deshpande Wed May 26 12:11:28 +0000 2021

Q: And the price of the dependency? I think of another poem of yours: Brief self-help manual.

A: Yes. But that one is more general, perhaps. It is not focused on journalists. I think we live in a time of herds. A time when there are many people who claim to be shepherded. That's what this poem is about. It is a series of tips for those types of people who claim to be shepherded by a third party.

Q: Is that something so characteristic of our time, or has it always happened?

A: Well, that's true. This is older than prostitution. I'm remembering Emilio Lara's novel, Time of Hope. It is inspired by the true story of a shepherd boy from a small French village who said that God had appeared to him and asked him to embark on a crusade of unarmed children to the Holy Land. The curious thing is that, either because some believed him, either out of desperation or because there were parents who could not feed their children, the boy formed an "army" of unarmed children. Of course, only on the way through France were many dying, for various reasons. They suffered kidnappings and that kind of thing. And when they finally got a ship they were tricked and instead of reaching Jerusalem they ended up in Alexandria, turned into slaves. The thing is that a high percentage of people have always needed to run away from reality and buy the cheapest lie there is. It is something that is digested better and, in the short term, can even provide benefits. But they are fictitious benefits that end up becoming boomerangs.

Q: Let's change the third. The collection of poems also touches on covid.

A: Yes. I started the book two years ago, but in the middle of writing it came across Don't give more whiskey to the dog, the novel about Raúl del Pozo that I was commissioned to write together with Julio Valdeón. There, wow, I stopped. But I liked what was written and I left it frozen. As poetry is not like prose, in the sense that it does not depend so much on breaking stones and maybe it does have a greater component of spark, of inspiration, during the writing of that book some other poem came out. But in general terms the matter was quite stopped. That's when the lockdown caught up with me. And confinement, for me, things as they are, literarily appeased me. He was not able to write, not just a verse, but a bloody article with a little more literary substance. I was like this for a couple of months until I published an article in Zenda that was about that, precisely. That was the engine that started up again and that brought me back to writing. I wrote a couple of poems about the lockdown as a result of that. But how did it really influence me? I do not know. I think they are quite journalistic poems. I don't talk about myself that much. I'm talking about the Ice Palace and such.

Q: This brings me to the poem The World Against the Poet. I guess it will also have to do with your journalistic facet. To what extent does the constant bombardment of current affairs inspire and to what extent does it shorten your wings?

A: Well, actually The World Against the Poet is a hyperliteral poem. It is that the neighbors above did not stop giving for sack. It's about that. There is no double reading or anything like that. But regarding the influence of journalism, I try to be influenced as little as possible. By professional training I already have the chip to write articles like someone who uses a meat grinder. I don't need too much effort to do it. There are days when one is more or less inspired, but it doesn't cost me anything. Writing poems is something else. To start I need that flash that I talked about before. But then you have to pull the thread, and take into account the metric. Rhythm. Everything. I wouldn't want that machinism that I have when writing journalistic texts to spread to my poems. Although it is inevitable that some things will transfer. Baudelaire I think he was one of the first to go to the suburbs of Paris to tell what he saw. I have already mentioned before many of my poems with that journalistic facet. The poem Children of the days of him, for example, I think it may be the most journalistic, without being completely. It is what I think of the ecosystem in which we move. But beyond the inevitable tics I have tried not to mix things up too much.

Q: Let's talk about metrics. Is denying free verse modern today?

A: It is that poetry has become a refuge for lazy writers. As Silvia Grijalba says, what prevails now is the bloody poetry of the enter. "The plant", enter, "looked", enter, "towards Carmelo's chamber". And uncles and aunts go and post that on Instagram, with a photo as if they were constipated, and they get thousands of likes. It's something that seems great to me, eh, I have nothing against it. What doesn't seem so great to me is that later a reputable publisher arrives and awards a literary prize based on the number of followers the author has. On the one hand, I take great care of the metrics for that reason. I am not from the tribe nor do I have a card. But, on the other, because it gives me a certainty that free verse doesn't give me. If I go and make a tenth I have to know that it has to be made up of ten lines of eight syllables with rhyme, consonant or assonance. Then you may like it more or less, but it fits in the dress. And I think there are a lot of troops who, out of laziness and vanity, throw away the first thing that comes to mind, they recite it as if the Virgin of Fatima had appeared to them and herding. Mine is not that nor do I want it to be. And this is not to criticize free verse poetry, of course. Luis Alberto de Cuenca, Ángel González, Gil de Biedma… There are enormous poets who have marvelously cultivated free verse.

Q: Man, but you are talking about three poets who dominate the meter, precisely.

A: Indeed.

Q: Is it necessary to master meter to make good free verse? Is rhythm more important?

A: And also ingenuity. Say really witty things. Ángel González's definition of the history of Spain comes to mind: "It's like blood sausage. It's made with blood and it repeats itself." In a poem of rhyme and free verse you can say very interesting things. What pisses me off is the abuse, the laziness and the vice that is installed in it. Something that has also become a business. And I say it with envy, huh. Because each one who buys and sells what he wants, more would be missing. But, damn, I'd like people to ask for more Quevedo and not so much Alfred García.

Q: Speaking of Quevedo, in your sonnets I perceive the influence of the poets of the Golden Age.

A: Yes, yes, yes. It is true. Before I mentioned three great references close in time. But Quevedo and Lope… Even Dante. My two favorite poems are the beginning of the Vita Nuova and "Who tried it, knows it", by Lope. I use the classics a lot. Six or seven years ago I made a list of books that had to be read and since then they have accompanied me. I've read the Divine Comedy, Paradise Lost, the first two volumes of Montaigne's Essays... With their parentheses, of course, as you well know, cultural journalists have to read a lot for work. Last year I dedicated a lot to Spanish classics. I was able to remove the thorn from Don Quixote, which I had never read. Although I have to say that the first part makes me a little sick with all the interspersed stories. The second is impressive. I cried at the end. And I laughed. It somehow reflects the soul of Spain. Don Quixote is dying and everyone is crying, but right away, when they start talking about the inheritance, they return to the world and their quarrels. Cervantes made an X-ray of the average Spanish that is still maintained.

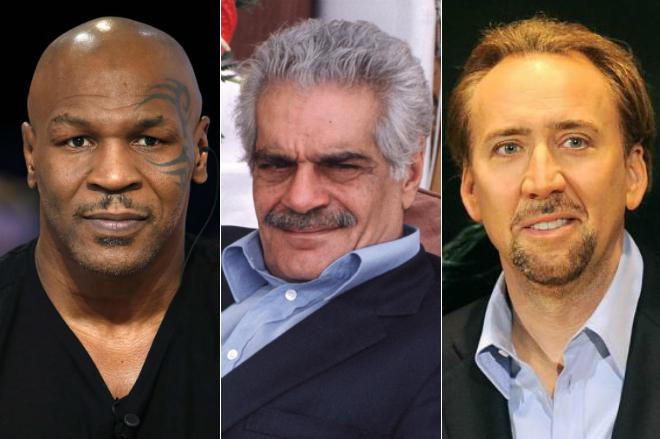

Q: You also dedicate four poems to very current people. Why them?

A: Well, to José Mota because he introduced me to the previous book after only having met me through an interview and a couple of conversations. Since then we have been friends and even he has taken me to his New Year's Eve program to make a cameo. He has always been very good to me and I wanted to thank him. To Emilio Lara because, well, he has never taken me to his New Year's Eve program because he doesn't have it, but he is also one of those guys who, since I met him, developed a very easy and deep friendship. With him I have something that I have with few people and that is that, when there is something that squeaks us or excites us, with a look and a nod we have understood each other. Another goes to Extremoduro. The explanation is not too mysterious. In the first collection of poems I introduced a section of poems to musicians that I really like. The one from Extremoduro left me in the inkwell, so one day when I was listening to Los Chichos I thought about it and got on. Hence the extreme Sevillanas. And the last one is for Battiato. He is an idol. The last time I came close to having Stendhal syndrome was at the last concert he gave here. (Think). Battiato is a guy who can make you dance and who you can listen to while you write. He is capable of making the most danceable and fun pop music —but educated, mind you, he has never sold fast food—, and at the same time music that puts you in a parallel universe. When you scratch a little it seems to me much more understandable than it appears to be. The logical thing is to say that Battiato does not understand even God. But when you do a little research, you start spinning concepts. (Think). The truth is that the poem dedicated to Battiato is written with great sorrow. While I was in Bologna it was published that he had Alzheimer's. It was immediately denied by the family. But it is true that since then he has not shown any signs of artistic life, beyond an album called Torneremo ancora and that had been recorded a couple of years before. I wrote that poem when he released that record. Then he died about a month after I delivered the book. And I thought: "Oysters". I don't know. There is a lot of guts in that poem because Battiato is one of the artists I have enjoyed the most in my life. I was very sorry for the way he faded away. Although it was super worthy, on the other hand.

Q: For ending in the least original way possible. Between the first and the second collection of poems, what has evolved?

A: There is a world. To begin with, I have studied. In the first collection of poems there were errors in metrics and internal accentuation. What happens is that you realize later. Now when I talk about it, as I wrote it when I was 27 years old, I say that it is a work of youth and I hope that the staff knows how to contextualize it. In this no. I have studied more on this one. In the sonnets I have tried to make the hendecasyllables melodic. Although I have also learned that there are emphatic, sapphic, heroic... I have tried to play with that. There are also tenths, couplets... And then there are structures that I've done with a guitar. There are undercover songs. I think that what I have looked for the most in this collection of poems has been the rhythm. He wanted the reader to be rocked by the poems.