The melting pot of the USA, with its cracks

In the United States, there is a problematic relationship with immigration. One of its main founding ideas has been the melting pot, even though governments have excluded different groups of immigrants for centuries. The so-called "nation of immigrants" even today leaves out those who were here before colonization (the original peoples) and those who were brought against their will (enslaved Africans). In other words, there is a gap between the romantic image of the United States that children are taught and its harsher realities.

Arrivals, a thought-provoking exhibition at the Katonah Museum of Art in Westchester County, New York, uses historical and contemporary art to probe that gap. Curated by art historian Heather Ewing, the show looks at how newcomers to this land have shaped it and been received.

In particular, the exhibition dispenses with the word “immigration” and chooses a somewhat broader term: Arrivals includes those who do not fit into the official lexicon. In its own way, the exhibition continues to defend the idea that it is a strange cauldron of peoples and ideas… except that it does not do so in a romantic or unrealistic way.

The exhibit begins with a timeline of US immigration and citizenship policies. It's a disheartening read, for the most part a chronicle of the exclusion that Ewing's argument makes: xenophobia is as foundational an aspect of American life as migration.

Ewing spreads over the timeline reproductions of contemporary political cartoons and personal commentary from some of the exhibit's participants, including Edward Hicks and Alfred Stieglitz, Kara Walker, and Cannupa Hanska Luger.

Guardians of moral conscience

These additions have the effect of making the artists seem faithful guardians of the national moral conscience, but for every cartoon that lambasts an anti-immigrant faction, how many have been published applauding one of them, I modestly wondered.

The exhibition is organized around seven “arrival moments” in US history. They start out specific, such as the 1492 landing of Columbus in the Bahamas and its effect on the original peoples there, and become ever broader, ending with the disappointingly vague category of "Today."

Although the show progresses chronologically, the moments serve as more than just content; They are also themes. In the first section, the works of art that mythologize the "discovery" of America by the famous explorer share space with others that criticize the destruction that he caused.

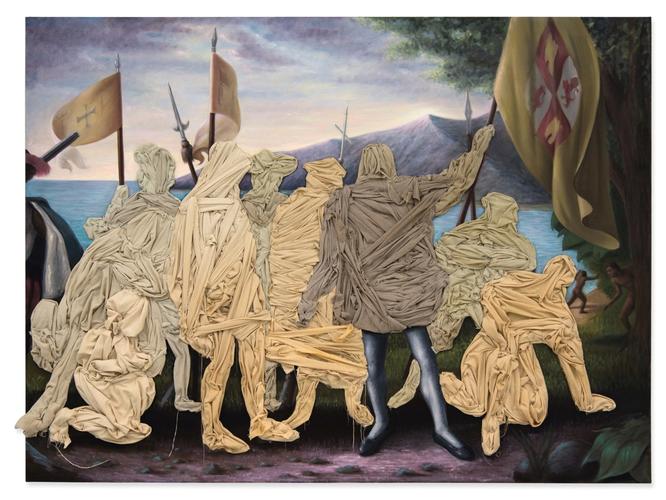

NC Wyeth's painting “Columbus Discovers America—note the royal Spanish standard—shows an emotional Columbus closing his eyes as he touches the earth with his sword and embraces his flag. This Wyeth sounds like a riff on John Vanderlyn's monumental painting “The Landing of Columbus” (1846) for the US Capitol Rotunda, which is represented in Katonah by an 1856 black-and-white print by HB Hall. The inclusion of Hall's copy, although small, helps to appreciate the great "Painting of the Day of Hispanic Heritage" (2014) -Columbus Day, the old Columbus Day is an important holiday in the country, with numerous parades-, of Titus Kaphar which is located nearby.

The piece borrows Vanderlyn's imagery but replaces the Spanish figures with blank canvas; puckered and wrinkled, the cloth that covers them mutes his heroism and alludes to the spread of disease. Kaphar is famous for this kind of historical review, which can sometimes seem gimmicky or overly witty. Seeing this next to the originals gives it a subversive force.

At its best, Arrivals provokes the sensation of witnessing discussions or conversations between artists through space and time…; It makes us understand what is at stake in those conversations. One of the most powerful examples is the part dedicated to the Middle Passage, the horrific journey of enslaved Africans to this land between 1619 and 1808.

As in the Columbus section, a small black and white print serves as a visual anchor. Created by Matthew Carey in 1789, it is a diagram of the inhumane crowding of people on the lower deck of a slave ship, an American version of the more famous British image spread by abolitionists.

“Plan of the lower deck of an African ship, with blacks, in a proportion not exactly equal to one per ton” (1789), black and white engraving by Mathew Carey. Credit...Colonial Williamsburg

history icon

Carey's print is sobering but its importance is also symbolic: the image of the slave ship becomes a recurring theme, an icon of history with which African-American artists must deal.

In “Estiba” (1997), Willie Cole transforms it into shackle marks, insinuating a relationship between slavery and contemporary domestic work. Keith Morrison makes us feel this more viscerally with a moody painting, “Middle Passage II” (2010), which puts the viewer in the position of a captive looking down. In Vanessa German's sculpture, “2 Ships Passing in the Night, or I Carry My Soul With Me Wherever I Go, Thank You” (2014), two black girls—created from found objects—carry model ships on their heads.

how to cook kangaroo steak on bbquae exchange melbourne

— Victoria Turner Mon Apr 20 10:30:02 +0000 2020

Instead of appearing crushed under their weight, they slide on a skateboard. It seems that the Middle Passage has gone from being a burden to becoming an essential part of who we are.

Ultimately, Arrivals is about identity, a topic that is trending in today's art world. What makes it original is that it uses a historical setting to address a familiar topic. The show isn't about race, ethnicity, or gender, though it touches on all of those things. It is about how artists can buttress, complicate, or unravel national myths through their stories and observations.

One way of doing this is by questioning the power of the state to document and confer identity. In the second gallery, spanning the 20th and 21st centuries, I was fascinated by the small but determined work “Solicitantes (Migrants, 2018), by Stephanie Syjuco, composed of three sets of passport-size photos with the faces of those photographed hidden by fabrics. stamped.

Annie Lopez created her funny and bold piece, “Show Me Her Papers and I'll Show You Mine” (2012), in response to the Arizona law that authorizes police to ask for documents from anyone they believe to be undocumented; she took personal documents of hers such as her birth certificate and awards she received in her childhood and printed them on tamale paper, shaping them into underwear. Despite the contrast between their strategies (hide vs. reveal), both artists humorously challenge a system that wants to catalog and control them.

Basically, Arrivals got me thinking about a question that is also the title of a timely Jaune print, “Quick-to-See Smith, 2001-03: “What is an American?” Smith's work features a headless primal figure walking absentmindedly as a kind of red, white, and blue rainbow springs from a stigma in his hand. It seems to suggest that the original inhabitants of this land were sacrificed for the sins of the new nation.

A short distance away, a photograph of Dorothea Lange taken shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor tries to answer Smith's ever-applicable question: It shows an American warehouse of Japanese goods with a sign in the window that reads, "I am an American." This claim of belonging was useless; the store was closed and its owner locked up in a prison camp.

Smith's title asks "what" an American is, not "who." In my opinion, this makes us aware of the artificiality of being an American: it is something that one becomes, a product of invention. The lesson becomes clear in one of the most lacerating works of the sample. "I remember my grandmother, Ellis Island" (1988), by Edward Grazda. The photograph within a photograph shows a hand holding, in front of a window, the image of a woman in a feathered headdress. The surrounding text reads: “My grandmother came to Ellis Island in 1912 from Poland. She had her picture taken as Native American.”

I dare say this is what it means to be an American: arriving here and reimagining yourself, often at someone else's expense.

Jillian Steinhauer covers art politics and comics. In 2019, she was awarded an Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant and was previously a senior editor at Hyperallergic.

Translation: Elisa Carnelli.

Arrivals. Location: Katonah Museum of Art. 134 Jay Street, New York. Accessible: at katonahmuseum.org

See also See alsoSole Otero: a legal squat in an inherited house

See also See alsoThe magnetic violence of “Titane”

TOPICS THAT APPEAR IN THIS NOTE

Comments

Commenting on Clarín's notes is exclusively for subscribers.

Subscribe to comment

I already have a subscription

Clarion

To comment you must activate your account by clicking on the e-mail that we sent you to the box Did not find the e-mail? Click here and we will resend it to you.

I already activated itCancelClarion

To comment on our notes, please complete the following information.