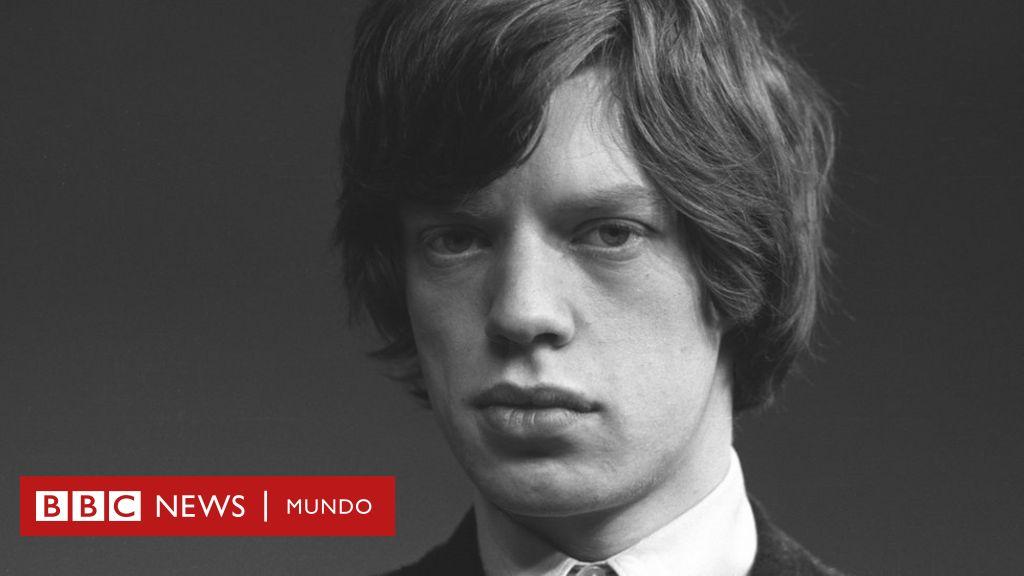

Mick Jagger: we recovered the interview we did when he was 26 years old

This article originally appeared in the June 1969 issue of Esquire. It's a historical profile of the Rolling Stones frontman (when you're done with it, we recommend our article on every Stones album from worst to best), but it contains an outdated and potentially offensive description of the race. We encourage you to read all of Esquire's articles published in Esquire Classic.

"Mick Jagger is probably the best performer to come out of the pop world. Erotic, moody, destructive, narcissistic, violent." -The Observer (London)

Even if you loathe Mick Jagger (don't miss the 50 photos from his prime for a radical style lesson), as I did at the beginning, you can't afford to ignore him, because he's a significant leader of the scene. of pop culture, perhaps more than anyone the voice and symbol of the new generation. At his best, visceral and demonic, he's able to make all other pop singers look puny by comparison. The endless procession of young men singing in a barely audible, childlike castrato style, or the monotonous, affected tone that makes many of them indistinguishable from each other; even the Beatles - especially Paul McCartney, with his sweet, thin voice and wide-eyed innocent face, looking like a twenties naive about to sing boop-boop-a-doop - none of them can match the menacing and blazing intensity that Jagger (you know the legends of His Satanic Majesty?) can bring to a song. His performance is a kind of flamenco pop: all fury, passion, authority and masculine arrogance.

I first saw the Rolling Stones more than three years ago on a British television pop music show. Mick launched his "cri du ventre" - I can't get no satisfaction - strutting, capering, jerking, face distorted, voice strident, a Corybant of seething energy. He was horrified. Most disturbing, though, was the realization that I was curiously angry, a reaction I couldn't understand, because my main interests in life don't include the ephemeral-as-foam Top Ten hit songs, or those who they sing them An examination of my initial response revealed that the feeling of wonder (which, in my case, soon turned to fascination) was one that I shared with older people all over the world. While they may dismiss other pop singers with boredom, annoyance, amusement, or contempt, Jagger provokes anger. With that latent misoneism common to most, they instinctively resent and resist his incendiary challenge to their comfortable citadels of compromise, built on the family rites and rules that, believe them or not, have come to represent the acceptable norm.

For this, the Stones are anathema to most over thirty. You don't see middle-aged matrons chirping about them, as they do with the Beatles ("The Beatles are just lovely!" said the late Dorothy Kilgallen on a David Susskind TV show), nor are they thrashing with long and elucubrated exegesis in magazines like the Partisan Review. Nobody calls them adorable, sweet, funny and cute; Jackie Onassis doesn't bring her children to listen to them; it would be unthinkable for the Queen to honor them with the Order of the British Empire; and the British ambassadors do not entertain them. On the contrary, they were recently referred to as "every mother's nightmare" by a London newspaper, and are loathed by millions of older adults who generally tend to regard them as the sort of social outcast one would expect to find in the world. neighborhood opium den.

So I approached my first interview with Mick with some trepidation. Though by then he was already a devoted, if not mesmerized, admirer of his talent, I was still intimidated by his reputation. After all, even The Village Voice had said that it "defies focus... Wanna touch Mick Jagger? You can't even get close." (The writer, Richard Goldstein, from the same age group as the Stones and a regular on the pop scene - which I certainly am not - also quoted a British journalist as saying that "talking to the Stones is like going to the dentist... [they] reduce reporters to heaps of stutterers and embarrassers").

Our meeting was scheduled for seven in the evening in the recording studio where the group was going to spend most of the night working on the songs for their new album, Beggars Banquet. I had been warned that Mick was never on time and that he was so unpredictable that he could show up hours late or not at all. The photographer, a friend, and I arrived early and waited in the empty control room. Right at seven o'clock, Mick walked in. He wore a long yellow jacket, violet pants, a lime crepe shirt with frills in the front, white socks, and dark brown and white riding shoes. There was nothing scruffy about him. His long light brown hair looked bright and proper (a buzz cut Jagger is a daunting idea) and his clothes were immaculate. He has the lean, taut, elegant body of a young bullfighter, and though some might find him ugly - the overly full lips, the pale, cold, pale blue eyes in the pale, cold face - there is a quality of unmistakable machismo that makes his iconic appeal instantly clear to young women, who have been known to crawl through the halls in mass hysteria at his concerts, writhing like eels on the floor.

Charlie Watts, the drummer, arrived shortly after Mick. He is quiet and polite and rarely smiles. He was dressed more conventionally than Mick and he explained to me that he had attended a baptism where he was the best man. He seemed worried that I would hold this against him, because later that night he came up to me and said, apologetically, "I didn't want to go to the christening, you know. It's not the kind of thing that... well ... it was my sister's baby and I only went because it meant something to her." "Was the baptismal font pretty?" Mike asked.

The others were obviously going to be late, so Mick suggested we go to a pub. He took us in a Jaguar owned by the group (he himself owns a dark blue Aston Martin, a 1937 Cadillac convertible, and a second-hand Citroën). At the pub it was he who took our orders, went to the bar and brought the drinks. He was nice in an easygoing, self-assured way. He gave me the impression that he wanted to avoid, or at least postpone, any questions from me. He mostly talked to the others, who were all his age, and the conversation there and also in the studio, after the others arrived, he gave me insight into why would-be interviewers break down in frustration. .

For the first hour I could barely understand a word he said. This was not solely due to the use of pop slang. Partly it was because he has a tendency to strangle his words (although when he wants to annoy, he expresses himself lucidly), but mostly because, when he talks to his friends, he uses verbal shorthand, a kind of empathic communication code Once you get the hang of it, which can only be achieved by tuning into the thought pattern, you begin to pick up at least some of the clues. For example, when I mentioned the name of a press agent, he said, "Yes, I met him today." There was a silence. Then he said, "I had a briefcase." That was it, but from that one sentence I had an idea. It wasn't always that easy, and I often had to ask for a translation.

Although he knows exactly what he's doing, he doesn't like to seem serious or businesslike. He pretends not to know anything about the organization of the group, but a partner told me: "He runs everything. He has lawyers and accountants, of course, but Mick makes the decisions. He is like the chairman of the board of directors. Others offer suggestions and he he can take them or leave them. He never makes a big production, but he's the brains and the guts of the team and what he says gets done, but without any phony hustlers."

He even brushes off questions about his songs. "Keith does them. I just help him," he said. Actually, he writes most of the lyrics and he knows what he wants in music, too, although the atmosphere that night in the recording studio was so lighthearted that an outsider might have thought that neither of them had the faintest idea of what he wanted. what he was doing. They sat idly by, joking around, looking at magazines, acting like they were killing time on a rainy Sunday, with nothing else to do. Any record company executive who had walked by would have had a nervous breakdown on the spot. For starters, they couldn't find one of the album tapes. "Didn't we have them in little cans?" Charlie asked. Not finding her in the room, one of the technicians went to look in the basement.

"It's a drag," Mick said. "Like a child looking for a marble: here is the one I lost two years ago, but where is the blue one?" After a while, another man entered. "They have lost

Parachute Woman," Mick said, "and now we've lost the guy who came looking for her." The guy who had just arrived went out looking for the first one. "Well, there's another one missing," Mick said. What were we doing the night we did Parachute Woman?" It was an hour and a half before they found her. "Do you know who found her?" Mick said. "The doorman found her." He didn't know if he was kidding or not. “How long are you going to be here?” “Well, I'd like to talk to you,” I said. Let's go to another room. This is something impossible.” So was he, because by then the sound engineers were at the controls and the bursts of music were turned on and off with bone-shattering volume.

He led us into a small, messy room, where we sat on a bench. He asked me how I was going to overcome the language barrier, but I didn't have to worry. He evidently understood my dilemma because, as soon as we were alone, he began to speak clearly, a concession he makes to outsiders, except when he wants to deliberately confuse them.

I started by asking him about Performance, the movie he was going to make for Warner Brothers-Seven Arts. "I hate the world of cinema," he said. "Press agents, producers and business people. They're so stupid. Press conferences annoy me so much. The reason you're doing it in the first place is because you're a pop singer going to perform at a Isn't that right? Why should I give interviews? To help sell the movie. Why do they want to sell the movie? To make money. Make money for whom? For them, the entrepreneurs. I guess that's a reason valid, but it's a reason that bothers me. It won't affect me because I'm not dying to become a movie star. I wonder why I should make a movie? I hope I enjoy making it and I hope I can use another part of my brain that has been asleep, but maybe I'm just doing it to promote my own ego. It's all hanging in all directions. That's why music is rhythm. I'm happy with that.... No, I don't want a personal business empire The Beatles opened a store. That's the dream of the English. No I want to fulfill it. They didn't either. Well, they want but they don't, if you know what I mean... The Maharishi? Yes, I went with them to Wales to hear it. He was pretty cool, but he had no desire to go to India. It's like... if you're looking for something, you want to try to find it. You want to find something. It's okay if you feel that way and you think it helps you. I don't feel like I need it."

And his trip to Brazil? "We were in Rio, living very large in the Copacabana, and then I was walking on the beach and I met some Brazilians who had a cabin a thousand kilometers north of Rio that they said we could have. It was near a village, but where we were there were only two other cabins with families. Thirteen children in total. We stayed a month. We had a great time, lying on the beach, playing with the children and dancing. We played the drums a lot. You know, the native drums , with black Brazilians. They have a lot of voodoo and a black saint and shrines. It's a mixture of the Pope and African voodoo. Very strange. They have a kind of vision, a fantastic vision that has nothing to do with the kind of incredibly limited economic vision If you ask a politician what his vision is, he will talk about export and import or tell you a lot of nonsense about helping people, but he is referring to material incentives, not humanitarian values, not a help people to be what they want to be, that is, themselves as human beings. We poison the air and water for commercial profit and cut down forests for newsprint. I don't see capitalism well, but Marxism doesn't seem to make life happier. In communist countries they are grayer than gray. Everything is a mess. We gave a concert in Warsaw and there were police everywhere. An American journalist asked me what I thought and I said, 'Yeah, it's horrible. Just like in Los Angeles. They are richer there, but there are the same number of armed policemen.' Most people don't think like that. Most people think of clichés they have heard or read that are nonsense. You realize they're not even really honest about it, and then they bring you down. They subscribe to the despicable ethic of valuing people based on their ability to earn money. They don't even know that they are not happy, they never enjoy the moment, they always work and plan for the future. They save money to buy a house, work thirty years and get their gold watch. They never take time to explore themselves. Society is wrong. All those scary vibes. The students are right: not only the setup and rules, but the whole concept needs to be changed. You have to learn to live in the moment and enjoy it. I don't mean to live for pleasure. I don't want to sound mystical, but I believe in living for every eternal moment..."

I told him that I had been nervous about meeting him, and he smiled. (He has a very charming smile, which lights up his entire face.) "It has been suggested," I said, "that the Stones deliberately created a mean and tough public image to differentiate themselves from the Beatles, who were considered so lovable." "God, I wish I was that smart!" he said. "The Beatles used to say very sarcastic and rude things to journalists, but nobody would write it down because it didn't fit the image. We were actually pretty awful to everyone because they were so awful to us. We didn't like it at all - all the interviews and so on - and we didn't like talking to them either because they were assholes. They didn't understand us, so we were in a really bad mood. We thought we knew everything, and in a way we did. People scared us into paranoia. They were rude with our hair and the way we dress. We're clean, we're not dirty and our hair shouldn't be important. What's important is the kind of people we are. In Wales, for example, we were hungry and we went into a place to eat. It was the Ritz, it was just a pub, but the guy at the door didn't even tell us, 'You can't come in because you don't have a jacket and tie.' He just took a look and said, 'No.' to an old man at the bar, so We asked him, "Do you agree with him? You have no rights. I'm still capable of punching you in the nose.' He was hysterical. If Keith had been with me, he would have hit him, because he has more of a temper. I am calmer. I don't want a scandal. Of course, when we were younger, you know, nineteen years old, we used to get angry and yell. It's other people who cause the problems. It is they who are rude and insulting. We don't stare at them and start making comments about how fat they are and how horrible they are. But our appearance infuriates them. People are so brainwashed by rules and authority that they don't know what really matters. They are afraid of teachers, of parents, of bosses, of fluff, of army officers. In Rome we met some Americans who were going to Vietnam. They didn't want to go, but they were going. They were afraid of what their friends and other people would think if they didn't - that they were cowards - or of going to jail, which I think is better than being shot. I can't even talk about it: the whole Vietnam thing, from start to finish, is so immoral and insane. It's so indefensible what can you say about it? "My country, right or wrong"? That is the dumbest slogan ever invented. All you have to do is think about what the words mean and you'll see how stupid it is."

now that i know how to cut a passion fruit i think i'm fully prepared to live on my own

— ᗢ Sun Apr 18 15:51:53 +0000 2021

The next time I saw Mick was at the Stones' office on New Bond Street. He had been in California for work on the Beggars Banquet album and there was already a dispute over the album cover which Mick helped design. He taught it to me. It represented a gas station bathroom in Los Angeles, with the walls covered in graffiti and part of the toilet seat showing. The color was beautiful - predominantly yellow ocher - and I found it striking. Of course it was original. "They say we can't use it because it's obscene," Mick said. I thought there must be something objectionable about the doodles on the wall, so I started reading them. They seemed harmless: no bullshit or anything, just lines like "Lyndon loves Mao," "Strawberry Bob for President," and references to songs on the album. "Decca has put out records with an atomic bomb exploding on the cover," said Mick. "I find that more offensive than a toilet. I'm going to insist that you use it."

(In the end, he had to give in. The album's release was pushed back two months while Mick held his ground. But he was expected to easily earn an estimated $2.4 million in the first few weeks, so the delay sent everyone into a frenzy, except Mick. For a time he considered putting it out through the Beatles' company, but was told that, under existing distribution contracts, the Stones might be sued by Decca. He finally reluctantly agreed to the substitution for a most innocuous cover).

I told him that I had heard that he had difficulties with immigration in the United States. "Not this time, but on the previous trip, after the drug thing, they interrogated me for two hours. They didn't do it in Poland. I bet they wouldn't do it in Russia. Only in America. They didn't understand what a conditional exemption, and I had a hard time explaining it.

As everyone knows, Mick and Keith Richard were arrested in 1967 following a police raid on Keith's country home and were subsequently convicted under the Dangerous Drugs Act. A Sussex judge sentenced Keith to one year in prison for allowing his house to be used for smoking weed and Mick to three months for illegal possession of four stimulant pills, which he had bought legally in Italy. (His London doctor testified in court that Mick brought him the pills and asked if it was okay for him to take them, but the judge ruled that verbal permission could not substitute for a written prescription.)

The sentences, absurdly disproportionate, provoked an immense controversy. Half the British population, according to an opinion poll, thought the sentences weren't harsh enough, but The Times editorialized against their harshness, publishing not unsympathetic interviews with the two beleaguered Stones, especially Mick. In one of them, the Times writer said: "There is no doubt that, in any survey of Britain's most hated men conducted among people over forty, Mr. Jagger would be near the top. Likewise, a survey among young people would reflect the special respect and admiration they profess for him."

The two Stones appealed to the High Court, which overturned Keith's conviction and overturned his sentence. Mick's sentence was reduced to a conditional discharge, which is similar to parole in an American court. The High Court's decision was followed by what was surely one of the most remarkable press conferences in history, a television showdown between Mick Jagger and what The Observer called "a show of force drawn from the ranks of the establishment," made up of by Lord Stow Hill (former Home Secretary and Attorney General), the Bishop of Woolwich, Father Thomas Corbishley (a Jesuit priest) and William Rees-Mogg, editor of The Times.

Mick asked to be interviewed outdoors instead of in a studio, so the television executives convinced Sir John Ruggles-Brise, Lord Lieutenant of Essex, to allow them to invade his estate with about thirty technicians, two vans and four large chambers. Mick, accompanied by Marianne Faithfull, was flown to the rendezvous in a helicopter, the pilot of which had the destination orders in a sealed envelope that was not to be opened until airborne. The drivers of the cars taking the distinguished interviewers to the scene were also given sealed envelopes, and the US Air Force halted all flights from its nearby base for three and a half hours, presumably so as not to break the silence deemed necessary for the occasion. . The resulting show, according to English television critic George Melly, "looked like a lost scene from Lewis Carroll".

Talking about it with Mick, I mentioned that what seemed to impress viewers the most was his patrician poise and calm, obviously disconcerting to his interlocutors. "It was full of tranquilizers," he said. "I kept swallowing them, so when I got there I was really scared. I thought it was really nice to be sitting in the garden with the Bishop and Lord Whosis and the others. They were fantastically nervous, standing up for their generation."

"About that generation gap, how do you get along with your own parents?" I asked for. He looked at me briefly, but then decided to humor me. "I'm not going to reiterate any hippie theories, but you just can't bridge that gap. It's impossible. I get along, I guess, but I couldn't say we're close. I don't see them much." "Are you proud of your success?" I insisted. "I guess so. I doubt they'll ever listen to our music. They don't like it; they don't understand it. They don't understand me, or who I am. That's not their fault, you know. It's just not possible for their generation to understand it." understand. Not really. We're not like them when they were young. We're something new, and it affects them. Some may have flashes of understanding, but most get nervous."

Michael Philip Jagger was born in July 1944 in Dartford, a town in Kent, where his father was a physical education instructor. (Mick is not a sports fan, and says that he hated rugby). He met Keith at Dartford Grammar School, although Keith left at the age of fifteen to go to art school in London. Mick's grades were good enough to get him a government scholarship to the London School of Economics. He arrived in London at the age of eighteen, in 1962, the year of the Beatles' first hit record, Love Me Do. Keith and Mick already had long hair - they didn't copy the style or anything of the Beatles - and they were both crazy about rhythm-and-blues records (they took the name of the group, Rolling Stones, from the Muddy Waters song, Rolling Stones). Stone Blues). At that time, the idol of British teenagers was Cliff Richards, a kind of young version of Pat Boone. (I heard him say on a recent TV show that he would like to do "a song that really said something in a Christian key.") Mick and Keith couldn't stand it.

They met Brian Jones at a Soho pub where they used to hang out, and the three of them played blues records and rehearsed together. They shared a seedy room in Chelsea: peeling wallpaper, a single lightbulb, cracked mugs without handles, a dark bathroom downstairs. "We were always broke and practically lived on mashed potatoes." Mick went to school every day, but in his spare time he sent tapes and wrote letters to everyone: promoters, club managers, record company people. Hardly anyone bothered to answer. A few times Mick and Keith sat down, just for the experience, on small dates with a rhythm-and-blues guitarist, Alexis Korner, whose pianist was Charlie Watts.

The Stones, as a group, made their first public appearance in the summer of 1962 at a small jazz club. They didn't charge anything. Then came a few late dates for which they were paid just over a dollar each. The day after Christmas, still in 1962, they won about $20 (for the whole group) for an appearance at a small club. Nobody clapped and it was a total disaster. From their beginnings, they were more basic, more earthy, than the Beatles, and they never compromised. They refused to play traditional jazz; they despised any trick; they never wore makeup on stage; they performed in street clothes; they didn't show big smiles or try to adopt a "showbiz" style. They were so different from what "entertainers" had always been that no one knew what to make of them. True jazz fans hated them; disc jockies made fun of them; one promoter who hired them said, "Honestly, I didn't know whether to laugh at them or send for an animal trainer." But less than a year later, in November 1963, they were to replace the Beatles as the number one group in Britain at the time.

What happened? What happened was its electrifying effect on young audiences. Word began to spread. They got a job in a club just over 15 kilometers from London, opposite a train station. There were only fifty people at his first performance. Three months later there were more than four hundred every night and more waiting outside. George Harrison went to hear them out and helped spread the word. They met Lennon and McCartney, who gave them the song I Wanna Be Your Man. They started recording albums and, although their first was number 50 on the Top Fifty, they won two popularity polls as favorite British pop group. When they appeared on television, jazz musicians wrote indignant letters; horrified parents turned off their televisions and forbade their children to buy the group's records; an angry citizen wrote to his newspaper: "Today I saw the most disgusting spectacle that I remember in all my years as a television fan"; and Melody magazine headlined an article, "Would You Let Your Sister Date a Rolling Stone?" Mick's comment was, "I don't even care if the parents hate us or love us. Most of them don't know what they're talking about anyway." When asked about his Aftermath album—"Why Aftermath?" journalists asked him—he replied, "Why not? We had to put something on the cover. We couldn't leave it blank." In Montreux, on the occasion of a television festival, they were asked to leave the hotel because, according to the manager, "they were not like the rest of our guests". Writer Pete Goodman, who is preparing a biography of the group, Our Own Story, called the principal of the school Mick and Keith attended in Dartford. "No comments. We don't want the school to be associated with them," the principal said, and hung up.

n the summer of 1964, the Stones made their first tour of the United States. (A British politician, in a speech, said: "Our relations with America are bound to deteriorate... Americans will assume that British youth have reached a new level of degradation.") When they performed before middle-aged audiences they were a flop. People yelled at them, "Cut your hair!", and when they put on a show with a horse that also acted, the horse received more applause than they did. No one liked them except a whole generation of young people. In San Bernardino they performed for 5,000 teenagers, and the girls tried to get Mick off the stage. (Physical actions by his fans are not uncommon: in Zurich he was thrown from a twenty-foot platform and almost smashed to pieces, while in Marseille a chair thrown by an overly crazed fan hit him in the face, causing a gash that he sustained. to be sewn up in a hospital. The next day she made two performances in Lyon with a bandaged head).

In 1965 they topped the US charts for six weeks, and a tour of twenty-nine cities in twenty-seven days earned them about a million dollars, although fourteen hotels refused them reservations. Their penultimate album, Their Satanic Majesties, released in the United States on Christmas 1967, sold 600,000 copies in the first few weeks. (Last summer it was number one in Japan and it continues to sell fantastically throughout South America.) Sobre este álbum, Jack Kroll, de Newsweek, escribió: "La excelencia revolucionaria de trabajos como los de los Stones y los Beatles... se ha convertido en el hecho cultural más sorprendente de nuestro tiempo". En un año, los Stones vendieron diez millones de discos sencillos y cinco millones de LPs; y los fans pagaron más de 4.800.000 dólares para verlos en concierto. Sus ventas totales de discos, hasta el verano pasado, habían superado los 72.000.000 de dólares.

La actitud de Mick hacia todo esto sigue siendo despreocupada. "Nunca quise particularmente ser rico. El dinero hace que la gente sea muy peculiar". También las hace muy cómodas. Mick posee ahora una casa adosada en Chelsea de 120.000 dólares con vistas al Támesis, y hace poco compró a Sir Henry Carden una casa de campo de dos siglos con veinte habitaciones. Vive con Marianne Faithfull, la hija de veintiún años de una baronesa austriaca. Marianne debutó en los escenarios londinenses en 1967, en el Royal Court Theatre, con el papel de Irina en la obra Tres hermanas de Chéjov, recibiendo la simpatía de los críticos, que no fueron insensibles a su fría belleza de doncella de las nieves. También apareció en el Royal Court como Florence Nightingale en Early Morning, de Edward Bond, que retrataba una relación lésbica imaginaria entre la señorita Nightingale y la reina Victoria. Scotland Yard no lo vio con buenos ojos y amenazó con procesarla por obscenidad, por lo que la obra se cerró tras una representación en un club de domingo por la noche. El año pasado (1968) Marianne protagonizó la película La chica de la motocicleta.

El anuncio de que Mick y Marianne esperaban un hijo (posteriormente ella sufrió un aborto espontáneo), pero que no tenían planes de casarse, hizo que el arzobispo de Canterbury comentara que se trataba de "un ejemplo terriblemente triste de la forma en que se ha desintegrado nuestra sociedad", a lo que Marianne respondió: "Los dos estamos muy contentos por el bebé, ya ninguno de los dos nos importa realmente lo que diga la gente". Preguntado en un programa de televisión de David Frost, Mick dijo: "Todo el asunto de la boda es muy pagano. Es una cosa de iniciación, y realmente no lo necesito. El trozo de papel firmado es la parte que carece por completo de importancia para mí... Si dos personas son razonablemente comprensivas y se aman, no deberían preocuparse por trozos de papel... Eso es lo que intento explicar. Si no fuera así, me callaría, ¡y tal vez debería hacerlo!".

Resulta que Marianne sigue casada con John Dunbar, un ex estudiante de Cambridge y antiguo marchante de arte, con quien tiene un hijo, Nicholas, que ahora tiene tres años. Se han iniciado los trámites de divorcio, aunque Mick mantiene su oposición al matrimonio, matizándolo ligeramente al decir: "Si la mujer con la que estoy creyera en el matrimonio y sintiera que necesita ese tipo de seguridad, se la daría. La mujer con la que estoy no es de ese tipo".

Cuando Mick estaba rodando Performance en Londres, fui a verlo. Era su primer papel como actor. (Los Stones aparecieron como grupo en One Plus One, de Jean-Luc Godard, pero esas escenas se rodaron durante una grabación real para el álbum Beggars Banquet). También era el primer trabajo de dirección del director, la primera aventura del codirector en esa línea, el primer intento de producción del productor y la primera película del productor asociado, hermano menor del director. No era de extrañar, por tanto, que el ambiente estuviera lleno de tensión durante los primeros días de rodaje. Aunque Mick había dicho que podía llegar en cualquier momento, cada vez que aparecía los nerviosos agentes de prensa empezaban a emitir vagos maullidos de angustia y me llevaban de una habitación a otra en un esfuerzo por mantenerme fuera de la vista del director, que también era el autor del guión. Cuando vislumbré a Mick, apenas le conocía. Tenía el pelo teñido de marrón oscuro, estaba muy maquillado y llevaba unas mallas negras ajustadas y un top. Me pareció que parecía avergonzado y debería haberlo estado. En la pantalla de televisión su rostro tiene una dura masculinidad, pero aquí, con ese traje y todo el lápiz de labios y el maquillaje de ojos, parecía que estaba interpretando a algún catamito de una corte medieval. En realidad, en la película se supone que es un antiguo cantante de pop que vive recluido, experimentando con formas musicales electrónicas. Su santuario es invadido por un gángster en plena fuga, interpretado por James Fox, y el enfrentamiento entre estas dos personalidades tan diferentes es el tema de la película.

Las primeras escenas que me permitieron ver no me parecieron gran cosa. Mick había estado en el plató todos los días a las ocho de la mañana, una hora sin precedentes para él, ya que normalmente se acuesta a las cuatro de la mañana. Además, está acostumbrado a dirigir las cosas por sí mismo, pero ahora le decían lo que tenía que hacer en cada momento: dónde ponerse, cómo sostener la cabeza, qué tono de voz utilizar, qué movimientos hacer. No se podía esperar un Paul Scofield instantáneo, por supuesto, pero la molesta supervisión parecía robarle toda su espontaneidad natural. Al fin y al cabo, estaba interpretando a un cantante de pop, no a Winston Churchill, así que me parecía que su idea de cómo se movería y reaccionaría el personaje debía ser tan válida como la de cualquier otro. El director fue inflexible. Mick debía acercarse y coger una bola de color de un cuenco. Primero lo hizo muy despacio, luego muy rápido, luego muy despacio para adaptarse al director. Sus frases eran del tipo: "Catorce bolas. Catorce bolas. Malabarismo, burbuja, malabarismo burbujeante en el escroto de Dios". A ningún ser humano se le debería pedir que pronunciara esas frases ni siquiera una vez, pero a Mick se le hizo repetirlas una y otra vez. Después de la decimosexta vez no pude soportarlo más. Cuando me fui, pude oírle todavía entonar obstinadamente: "Catorce bolas". Era deprimente.

Las cosas habían mejorado considerablemente cuando volví en un par de semanas. Mick estaba alegre y parecía haberse adaptado filosóficamente a los caprichos de las rutinas cinematográficas. Llevaba menos maquillaje y parecía más él mismo. Estaba bebiendo vino con Anita Pallenberg, que también aparece en la película. "Era aburrido hasta que llegó Anita", dijo, "pero ahora es todo más rápido. Voy al plató y digo unas palabras y luego salgo y espero otra hora". "¿Crees que alguna vez querrás hacer otra película?" "Estoy planeando una en Marruecos la próxima primavera. Keith y Brian y Marianne y Anita y Donyale Luna y John Philip Law- todos ellos estarán en ella conmigo, espero. Lo haremos nosotros mismos y lo haremos como queramos".

Hablamos de sus últimas canciones, sobre todo de Street Fighting Man - "Es el momento de luchar en la calle"- y me dijo que había participado en una gran concentración contra Vietnam y que había estado en la famosa manifestación frente a la embajada estadounidense el año pasado. "No he visto tu foto". "No lo hice por la publicidad", dijo secamente. Le mostré un recorte de prensa en el que se decía que el Departamento de Defensa de Estados Unidos estaba investigando un informe de un grupo de científicos según el cual los tanques de gas nervioso almacenados por el Ejército cerca de Denver constituían una amenaza para los habitantes de la zona. Los científicos, según el periódico, estimaban que en los tanques había más de cien mil millones de dosis letales del gas y que el tres por ciento de esta cantidad era suficiente para matar a la población del mundo. Mick sacudió la cabeza y se echó a reír. "Eso significa que tienen un noventa y siete por ciento más de lo que necesitan para matar a todos los habitantes del mundo. Tío, ¡es tan enfermizo, es tan raro! Nos hablan de responsabilidad. Ya sabes, como ese juez que me dijo que tengo la responsabilidad de dar ejemplo. Si tengo una responsabilidad, es la de ilustrar mi idea de lo que es correcto y justo y humano. Mi idea no parece ser la suya"

Antes de conocer a Mick, le dije a un amigo suyo que temía encontrarlo egoísta, frívolo e insultante. "Él no es así en absoluto", dijo el amigo. "Es un tipo muy decente e inteligente". And he was right. Cuanto más veía a Mick, más lo respetaba. No es, realmente, una cuestión de lo que dice. No se le entiende hablando. La mayor parte está en su música. Expresa lo que piensa y siente a través de ella. No cree que sea necesario explicarlo a través de una conversación convencional. Sus actitudes se comprenden estando a su lado. Es muy honesto y no finge una conformidad con normas que considera hipócritas o estúpidas. La gente que le detesta es aquella para la que él cristaliza su malestar por la juventud iconoclasta de hoy y la creciente erosión de la mitología ortodoxa. Lo que le hace tan exasperantemente insufrible para ellos es que parece saber que tiene razón y que ellos están equivocados. Sin embargo, lo que piensen de él es irrelevante tanto para él como para ellos. Él es el presente y el futuro. Ellos son el pasado.

Via: Esquire US