What is the SI and why it is one of the truly extraordinary achievements of humanity

From the moment of our conception to the end of our lives, from the inconsequential to the essential, everything about our existence is weighed and measured.

We are a species obsessed with quantifying things, because objective measurements ensure that we all get a fair deal.

But it is much easier said than done.

Fortunately, there are hundreds of people all over the world looking for the best ways to weigh and measure everything: metrologists.

Metrologists push measurement to the limits of technology. And they measure everything from the sheen of cat fur and the acoustic crackles of cookies to the fastest speed, shortest distance and greatest volume.

Its work is crucial: it has the potential to change every aspect of our lives, from economics, medicine, industry and technology to the cake you bake in your kitchen. Accuracy can make the difference between helping someone or hurting them.

That's why they've worked for centuries to ensure there are accurate clocks, consistent rulers to measure by, and equal masses to weigh.

To do so, they have created standards so essential that their very existence underpins the workings of our world, unchanging constants in a world that is constantly changing.

YES

In one place in Paris, the International Bureau of Weights and Measures or BIPM, an international guardian of metrology, houses a truly extraordinary achievement of humanity.

A list, or rather, a system of definitions: The Systeme International, or the SI, a scientific method for expressing the magnitudes or quantities of important natural phenomena.

It's a simple list, distilling all the essential properties of our world into just seven base standard unit definitions:

- meter, for length;

- kilogram, for mass;

- second, for time;

- kelvin, for absolute temperature;

- ampere, for electrical current;

- mole, for the amount of substance;

- candela, for luminous intensity.

It is also a powerful list, because by sharing it you can compare everything in every country on the planet in an easy and transparent way.

All our rulers, clocks, thermometers, and scales are calibrated against these essential standards, and they provide the basis for all kinds of measurements needed for science, society, and quality of life.

"Do you know how many languages are spoken on our planet? 3,000 different languages (6,909 when the rarest ones are included)!" physicist Jens Simon told the BBC.

"It's very complicated for one group of people to communicate with another, so having a universal language in measurement is a global story... it's very, very beautiful."

From the dawn of civilization

Measuring is a simple idea and humans have been doing it since time immemorial.

Thousands of years ago, people measured things with stones and grains to set standards. Those consistent measurement benchmarks revolutionized trading.

Naturally, people gravitated toward standards that everyone can access... like a hand, or an eye, or an arm.

But these seemingly democratic standards were problematic: if you measure a table with your hand and I measure it with mine, the sizes will most likely be different.

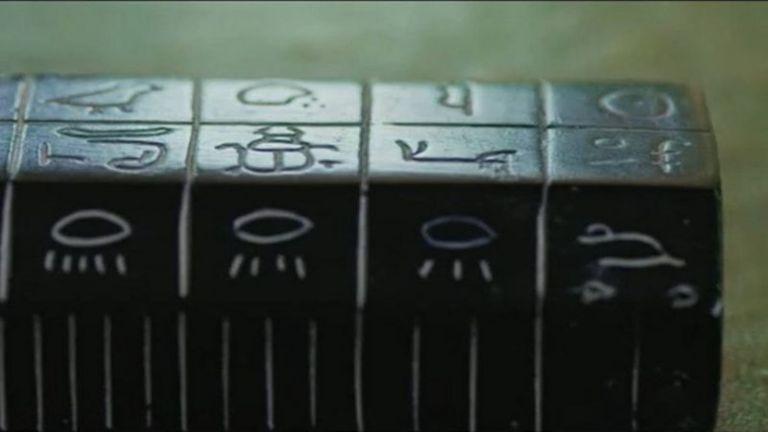

Because of this, many ancient rulers created stable standards of measurement throughout the empire.

In ancient Egypt, for example, the cubit was a unit of length that was sometimes the distance between the elbow and the tip of the middle finger or that distance plus one hand.

But they realized that those kinds of anthropometric units weren't going to allow them to build the pyramids with the kind of precision needed, so they created a standard: an artifact.

Standardized measures with artifacts allowed those in power to better build, rule, and tax their empires.

But over the centuries, these measurement standards massively multiplied and confused metrology through the creation of more and more units.

Pounds, ounces, stacks, charlemagne, yards, avoirdupois, shaku, pints, Ls, miles, feet, cun, shekel, inches...

In the 18th century, the list was so long that some merchants were dealing with 800 different units of measurement and a quarter of a million definitions for them, many of which were not comparable.

And these inequalities caused serious discontent among the masses.

In fact, baguettes and bakers played an important role in the French Revolution.

Let them eat 'brioche'!

One of the things that most worried the revolutionaries in France was the lack of impartiality with the measurements.

Bread was the main component of the diet of the French working class. The average eighth-century worker spent half his hard-earned money on it.

It was so important that the king controlled all aspects of bread production, including the price.

With France in the midst of a historic famine and different standard units of measure in each town, weights could be manipulated. So people often paid the same for less, and the poor had no way of proving that this was happening.

The peasants were hungry, angry and disgusted. France was in crisis.

Obviously, the causes of the Revolution were much more complicated than the price of bread, but it was one of the straws that broke the camel's back.

When the revolutionaries took power, it was recognized that one of their priorities would be to put in place a fair measurement system, so it was decided in 1791 to commission the French Academy of Sciences to develop it.

For everyone, forever

On April 7, 1795, true to its motto, A tous les temps, à tous les peuples, or "At all times, to all persons," the metric system was formally enshrined in French law.

This idea of a democratic approach to measurement was not based on the length of a king's foot or anything like that, but rather on constants found in nature, just like in the old days, only in a much more scientific and global way.

A meter, for example, would be a fraction of the Earth's circumference, which anyone could access and no one could change.

But at the time, that proved too difficult to measure accurately and consistently.

So they decided to create physical reference points for these new units: they made artifacts.

One of the first decisions of the National Assembly was to create the first metro. Then, they defined a new unit of mass that was the mass of a liter of water and called it the kilogram and made it out of platinum.

Thus was born the system that we have maintained for years... although, of course, with some adjustments.

Atoms, light, quantum physics

The second, for example, used to be 1/24x60x60 of a day. But at the beginning of the 20th century it was already clear that a day was not something constant, so they changed the definition of time with a fundamental, unchanging and universal constant.

Today, the definition of time is based on atomic standards, on the unchanging frequencies of atoms.

Artifacts that were used as standards were replaced with constants that could not be destroyed, worn, or stolen.

The meter, which used to be a stick, is now a measurement based on the speed of light in a vacuum.

The kilogram, the latest artifact, was redefined in 2019 by a highly precise mathematical constant, Planck's constant, central to the theory of quantum mechanics.

But despite these profound changes that moved the reference away from objective reality from a man-made artifact to an immutable constant in the universe, the idea remained to have a common and fair system for everyone everywhere in the world.

"When we do a good job, no one notices...and that's a good thing," says metrologist Edyta Beyer.

"What people eventually notice is the difference when new technologies start to integrate into better science," says Dr. Alan Steele, Canada's chief metrologist.

"The better we measure something, the wider the world of opportunity for scientific exploration becomes."

* This article is based on part of the BBC documentary "Measuring Mass: The Last Artifact"