The secret history of the kidnapping of Cristián Edwards

A 18 años del secuestro de Cristián Edwards, CIPER revela detalles hasta ahora desconocidos de uno de los episodios que marcaron la transición. El relato del cautivo –ex presidente de la División de Servicios Noticiosos de The New York Times y ahora vicepresidente de El Mercurio- y los graves conflictos personales entre sus celadores que hoy revelan ex miembros del FPMR, son algunas de las nuevas piezas del puzzle. «Varias veces me escapé en sueños. Otras fui liberado con intervención de sirenas y helicópteros», declaró Edwards al recuperar la libertad. Tras vivir durante cinco meses en una «caja» de tres metros por dos, recordó que se aseaba con una olla, que lo sedaban y que sufría alucinaciones, calambres y temblores: «Me tironeaba los pelos de la barba para arrancármelos». El encierro también afectó a uno de sus celadores, que fue amenazado de muerte cuando se decidió a abandonar la casa-retén. Su deserción, dada a conocer por un informante al gobierno, fue la primera prueba de que el FPMR estaba detrás de la operación.

See also: - The secret story of the kidnapping of Cristián Edwards II– The secret history of the kidnapping of Cristián Edwards III

After nine o'clock at night, after leaving the elevator and starting walking through the public parking lots of Cayancura street, surrounding his office in Providencia, Cristián Edwards saw them.Three young men around a white car.He saw them and did not attract his attention until seconds later, when he was about to enter his car and listened to an accelerated taconeo behind him.Then he turned and saw them again: the three came over him and one of them pointed to his head with a revolver.

"I thought they were going to steal my wallet, or something like that, so I raised my hands," he will say five months later the son of El Mercurio's owner, a few hours after his release, in a testimony to the police who has remainedunpublished."I didn't shout anything ... Two of them tied me, they put a plastic hood, they tied cables and among the three they turned me, they grabbed me and put me to the car that was parked."

The pipe of a revolver was practically the last thing he saw from the outside world that year.It was on September 9, 1991 and the then regional newspaper manager of El Mercurio and since July of this year Executive Vice President of that company, considered the natural successor of Agustín Edwards Eastman, would live from those hours and for the next 145 dayswhat he called "the box."A mousetrap of two by three meters, without windows or fresh air or company, in which he was almost permanently exposed to strident music, artificial light and the surveillance of his wardens that watched him from the outside through viewers.

Never, in the next five months, left there.He never saw another person's face.If he had something to say, he had to write it.If he took a step, he ran into a wall.If he showed signs of guidance, they gave him again with medications that he consumed next to the meals and altered the routines."The idea was to go crazy," summed up in the police statement of February 1, 1992. Five days later, before Judge Luis Correa Bulo, he would give a more extensive account of the captivity he suffered at the hands of a group of the Manuel Rodríguez Patriotic Front(FPMR) and whose details so far had never come to public light.

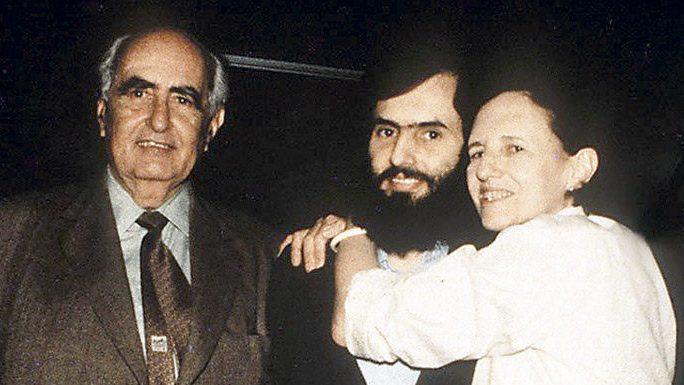

18 years after the event occurred, and when its protagonist has just left the presidency of the New York Times news division and prepares to assume the direction of El Mercurio, we go to testimonies and unpublished documents to recreate the kidnapping thatIt marked the Chilean political transition.

#Soyciperist

Support independent journalism